Formative Assessment Design 2.0: Building Students Toward a Better DBQ by Focusing on Image Analysis

Posted on Jun 25, 2019 Leave a Comment

Context and Purpose

As I’ve written before, Document Based Question (DBQ) is critical for the Social Science student and provides the ultimate application of historical thinking and reasoning. It requires that students read various sources and understand them such that they can cobble together enough information from multiple sources to respond to a question. Ultimately, transference to the contemporary world is the goal, either as a powerful tool for interpreting contemporary events or applying this skill to the workplace.

The DBQ is not often used in the average Social Science and History classroom. Advanced Placement (AP) classes use them as part of the learning and assessment process to prepare students for the AP Exam. Nevertheless, the average student and curriculum ought to use more DBQs—however challenging they may be. The typical DBQ asks a higher order thinking question that can only be answered by evaluating various sources, typically maps, images, or written statements from a particular historical period. Students write a response to the prompt by using the documents as evidence for an argument or historical claim. Students then write a response to the prompt.

Depending on the designed outcome, the DBQ is the ideal assessment. Typically teachers want their students to learn how to synthesize multiple pieces of information into a coherent argument, usually around other reasoning skills like Cause/Effect, Continuity/Change, and Compare/Contrast. A typical question in this order might be “Using the following documents, evaluate the extent to which European perception of Native Americans changed or stayed the same from 1500-1850” These types of questions assess a variety of skills and competencies, but they are time-consuming to create and grade.

The DBQ requires analytical, reading, and writing skills, among others. It is unrealistic to assume students have each one of these skills already. Like math, one missing skill can lead to a critical mistake that calls into question the entire problem. To that end, we need to make sure that each skill is given proper attention.

Perhaps one of the most fundamental skills that need to be taught is the ability to read images. Different from reading a text of words, students need to practice reading the text of political cartoons, photos, graphs, charts, and maps. From these sources, students should ultimately be able to identify the image subject, specific content, argument, and finally, the bias or point of view (POV) of the author. Formative assessments on these “essential skills” will be vital for student success.

Assessment Instructions for Learners

Students will be provided with the following instructions and take part in the learning assessment:

Class Activities and Learning Agenda

• You will first share your prior-knowledge of Native Americans and their relationship with Europeans by sharing with your peers in a group Flipgrid. • You are free to talk about anything you know.

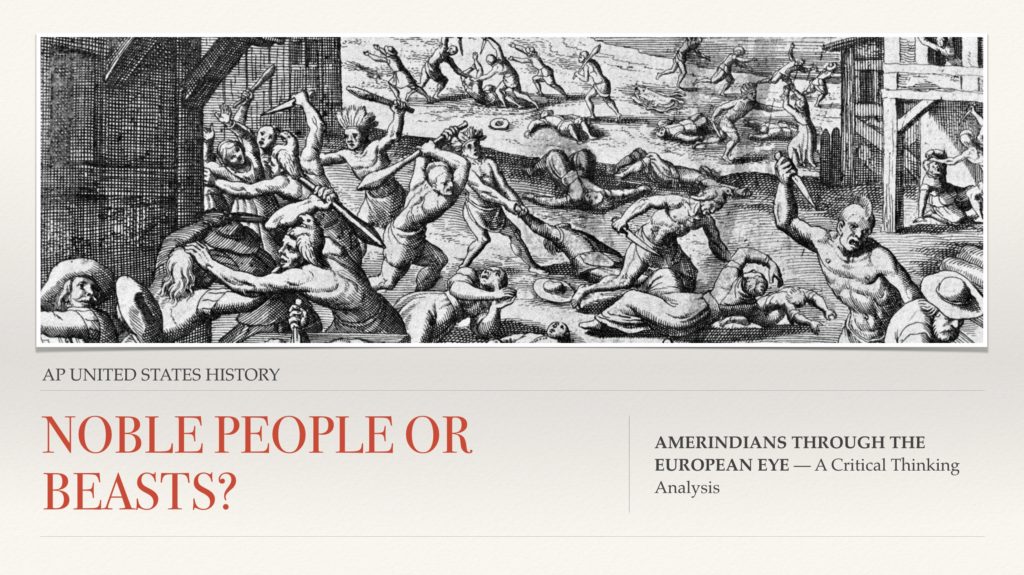

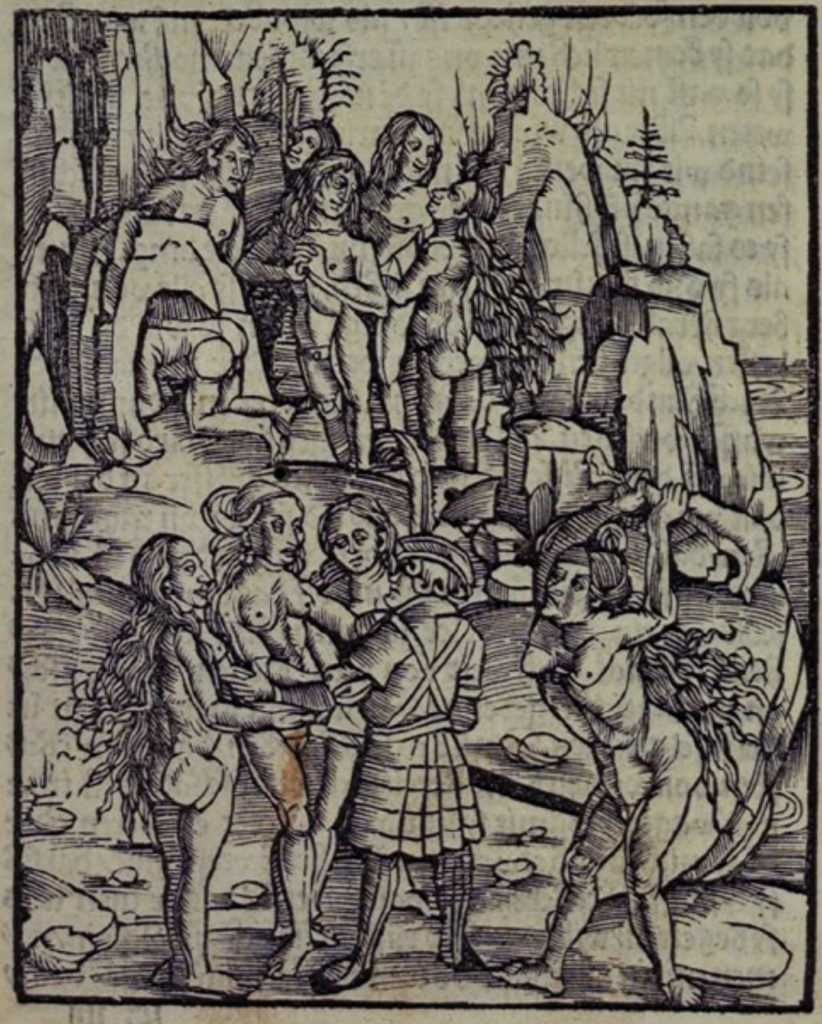

• You will then take part in a class observation of a few etching of Native

• Americans by contemporary European artists from 1500-1850. These images are part of a Keynote presentation entitled NOBLE PEOPLE OR BEASTS? AMERINDIANS THROUGH THE EUROPEAN EYE — A Critical Thinking Analysis. For each image displayed, you will shout out nuances, details, and reflections on the pictures shown. Your teacher will prompt you to reflect on the values and ideas of Christian Europeans. Consider what religious ideas and structures they hold. What figures (like the motif of Adam or God creator) were essential to their belief systems?

• With a partner designated by your teacher, you will choose one of the following images to analyze in the same manner as done above with the whole class. Students should consider the author of the image, the audience of those consuming the image, and the specific details associated with the image (figures, actions, tone, religious imagery, etc.).

• We will then work on a collaborative board for each image using Padlet in which each group (and others who want to help), can write key words, observations, and ideas under each picture.

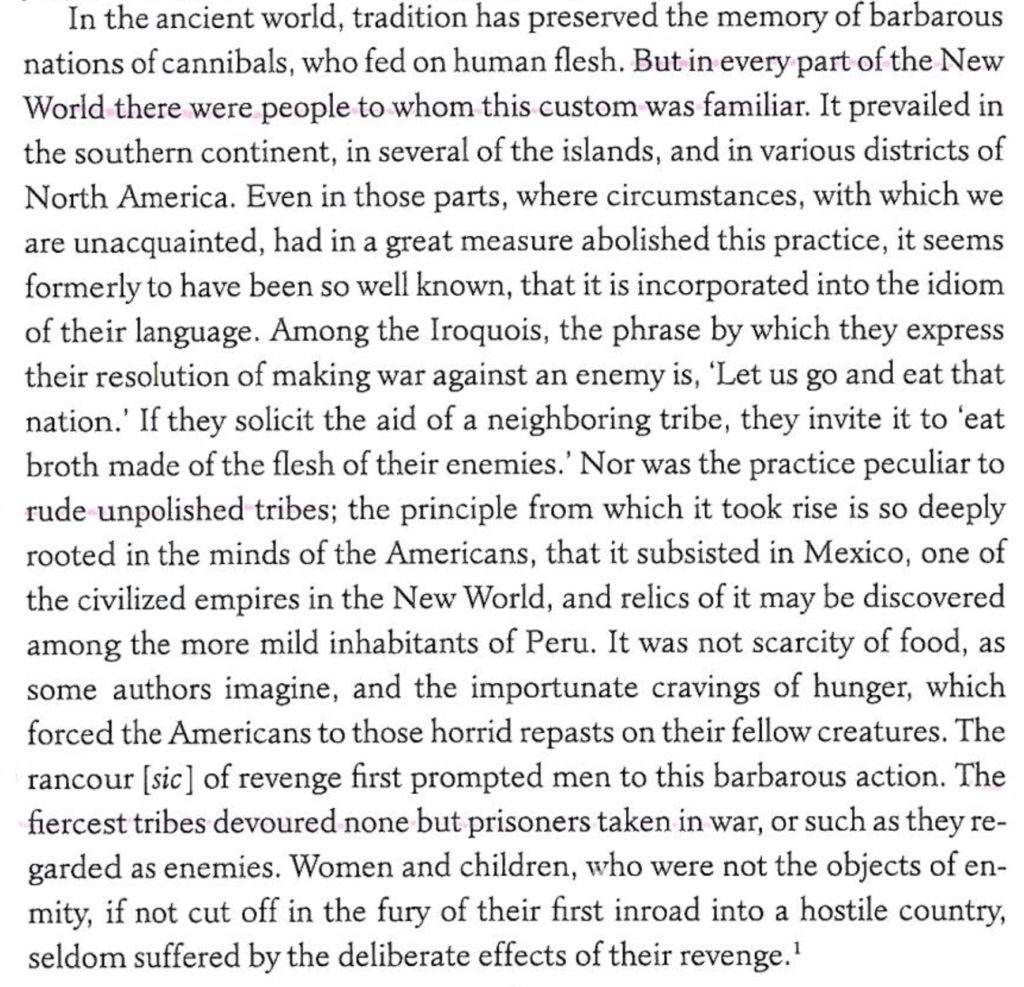

• After a quick discussion of our work on the images, we will read a brief primary source passage on how Europeans viewed Native Americans from 1844, an excerpt taken from a children’s history textbook.

• (SIDE QUEST) For those student teams whom both do not know how or have not used Flipgrid or Clips before, you get a little extra boost! I will work with your team individually to get your up to Flipgrid-speed (and discuss your image a little…shhh, don’t tell).

Assignment Instructions

In collaboration with your partner and through creative use of Clips and Flipgrid on your iPad, respond to the following prompt using evidence from the sources discussed in class, with your partner, or for the “extra” ones out there, your own discovered sources (not required, but if you are up for the challenge, let me know!):

Evaluate the extent to which European perception of Native Americans changed or stayed the same from 1500-1850

Assignment Submission

• Make sure that your video is under 5 minutes (time limit on Flipgrid)

• Make sure that you pushed your creativity.

• Make sure that you pushed your critical thinking.

• Make sure that you used all the documents (images, texts, etc.)

• Make sure that if you have questions, you ask!

• Make sure that you have fun!

Feedback and Instruction

Upon submission of the Flipgrid, the videos will be placed in a holding spot awaiting teacher evaluation and feedback. I will give verbal video feedback for each video, highlighting specific aspects of the content and process of learning and use of technology for creativity.

Students will be free to change any content or technical/creativity aspects of the project after I give the feedback. I can also give further feedback if so needed and/or desired.

Once the video is complete to your liking, your Flipgrid video will be posted to our class page where students will watch and evaluate each other’s amazing work.

As a formative assessment, the point is that students are growing and learning through the process. The following skills (as well as some content knowledge) analyzing images, using more than one piece of evidence, and using evidence to respond to a question. These same skills will eventually be used and applied with other types of media, graphs, and charts in future assignments.

Assessment Design Checklist 2.0

Posted on Jun 16, 2019 Leave a Comment

If you’re like me, my mind gets swamped amid all the things I want and need to recall and apply in my classroom each day. Assessments (aka, everything done in the classroom on a daily bases) can be overwhelming.

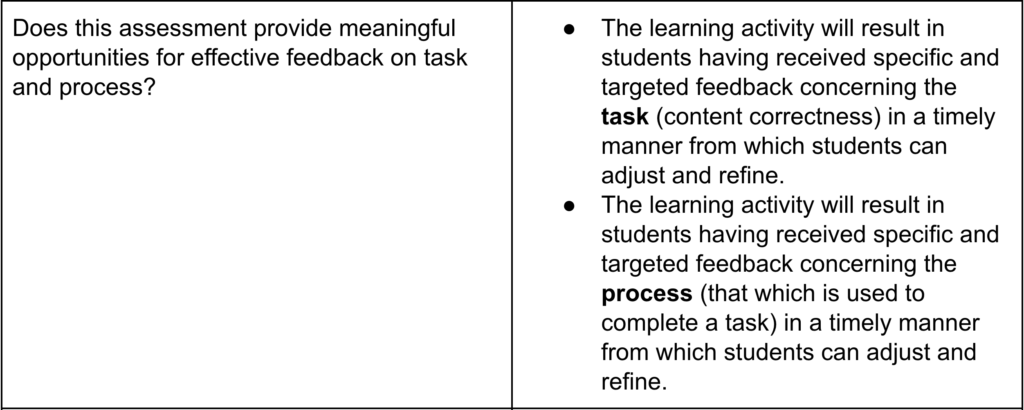

I am writing an assessment checklist to go over each time I plan learning activities for my students. In an early draft, I emphasized critical thinking and creativity as crucial components for my learning environment. For this iteration, I have focused on effective feedback on assessment tasks and the student process of accomplishing that task. I have also focused on self-regulated learning.

For the former, I focus on the quality and timeliness of feedback. Too often, I have provided students with poor (read: useless…shutter) feedback— things like “great job” or a “√” in the margin paper. I’m not a monster. I have given plenty of quality feedback as well, but never in a designed manner and certainly not consistently.

Concerning the latter, building students into independent learners who are self-regulated and can evaluate their performance and understanding is vital. Providing opportunities for students to reflect on their performance will help achieve deeper understanding.

I continue to develop this checklist and will post updates on my progress.

Click here to review my Assessment Design Checklist 2.0

I’d love to hear any suggestions or thoughts. Feel free to comment below with any suggestions or insights!

Effectively Teaching Critical Thinking through Document Analysis: Formative Assessment, Backward Design, and the DBQ

Posted on Jun 8, 2019 Leave a Comment

The Document Based Question or DBQ is not often used in the average Social Science and History classroom. Advanced Placement (AP) classes use them as part of the learning and assessment process to prepare students for the AP Exam. Nevertheless, the average student and curriculum ought to use more DBQs however challenging they may be. The typical DBQ asks a higher order thinking question that can only be answered by evaluating various sources, typically maps, images, or written statements from a particular historical period. Students write a response to the prompt by using the documents as evidence for an argument or historical claim. Students then write a response to the prompt.

Depending on the designed outcome, the DBQ is the ideal assessment. Typically teachers want their students to learn how to synthesize multiple pieces of information into a coherent argument, usually around other reasoning skills like Cause/Effect, Continuity/Change, and Compare/Contrast. A typical question in this order might be “Using the following documents, evaluate the extent to which political and economic factors led to the outbreak of the Great War (World War I).” These types of questions assess a variety of skills and competencies, but they are time-consuming to create and grade. Unfortunately, these types of assessment are underutilized. Too often, teachers turn to ready-made multiple-choice, matching, short-answers, and the occasional short essay. While many of these types of assessments have their place, they are best used to build toward the DBQ. In many ways, the DBQ provides a clear picture of what skills and knowledge a student has acquired and informs teachers on what skills and content they will need to review or adjust.

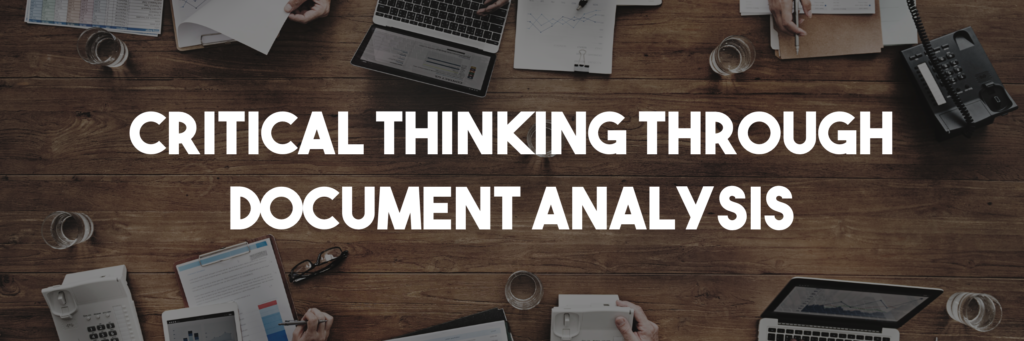

I am currently developing an Assessment Design Checklist that will be used to evaluate assessments, particularly formative assessments. In a yes/no style question, I have asked two critical questions: (1) Does this assessment allow for critical thinking? (2) Does this assessment allow for creativity?

I have written about this checklist and these questions previously, but this is the first time I am applying these questions to a particular formate or style of assessment. Click here for the Checklist which will be updated as I develop it further.

Using the information from “Evidence of Understanding” to evaluate this genre of assessment, the DBQ does indeed allow for critical thinking. However, the typical DBQ does not allow for creativity—at least in the conventional manner in which we think of creativity (drawing, acting, digital creation, etc.). It is possible to create a type of DBQ that utilizes student creativity, either with digital tools or with physical mediums. I will address this at the end, but again this approach is not typical for DBQs, as they usually are considered a type of formal essay.

The most challenging skill in the DBQ is critical thinking through document analysis. Reading the various documents, interpreting their meaning, and synthesizing their content as evidence in a well-crafted essay is complicated. Indeed, each one of these skills must be taught individually before assembling them in the DBQ. With this goal in mind, teachers ought to backward design the skills necessary to accomplish this task (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Students ought to start with reading and interpreting various sources of different genres. Images, narratives, poems, maps, and charts should be examined, and students should practice writing in response to particular documents. Gradually, students should be introduced to multiple sources from the same perspective in answering a question. Students should then be introduced to various sources that argue different things, but do not contradict each other. Finally, students should evaluate several sources from multiple perspectives that are contrary to or assert different truth claims from one another. Students will also need to learn how to write an effective thesis and how to use evidence effectively. Teachers might tend to isolate various skills and hope that by teaching each individually, a new whole will emerge where students assemble the essay from the parts. However, building upon the previous is vital to growth in this instructional design. In this manner, there are many opportunities for formative assessment and adjustment as student hone their knowledge and skills. Ultimately, the ability to synthesize sources and create a coherent historical argument is the primary skill and task of the historian.

While the AP Exam assesses learning through this method and college professors assign research papers that require the same skills, today’s technology allows for even more exciting and meaningful opportunities. Students are no longer confined to paper and stagnant sources. Indeed, they can engage with old music, the audio recording of speeches, video of past events, and even news and film. Beyond source material, teachers can also shift into digital DBQs, not as a typed document in a substitution for paper, but as a real transformation of learning.

This is where the creativity can come into this type of DBQ. Students can create a video using various media as source material to create an argument for their thesis. Perhaps they can create a video on the top 3 causes of World War I, post the video to a Youtube channel, and engage with classmates or the public in discussing and defending the analysis. The possibilities that technology provides is boundless in transforming student learning.

Teaching students how to use these tools and other creative skills can and should be taught to students throughout the year along with the critical thinking. One need only think about the desired outcome through a contemporary medium and backward design, teaching the requisite skills throughout the class.

References

Wiggins, G.P. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Assessment Design Checklist 1.0

Posted on Jun 5, 2019 Leave a Comment

Often deciding what to teach and how is haphazard and can feel like you’re flying by the seat of your pants. I must confess, I have pondered to myself on more than one occasion, “man, what am I going to teach them tomorrow?” No design with the end goal in mind was present in my mind on those few-and-far-between days (read: more frequent than I’d like to admit).

I am in the midst of developing a design checklist by which my future assessments and activities can be evaluated. This checklist takes into account a Backwards Design or UBD approach to instruction. This is an early draft with only a components son far. I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1qoNS7EfHZCg_dThqnrniz8vkZ_ZNNXggPKrfOEanDgU/edit?usp=sharing

ONLINE DISCUSSION AND BUDDHISM: FLIPGRID & FORMATIVE ASSESSMENTS

Posted on May 26, 2019 Leave a Comment

AP World History has just gone through a significant redesign this year that has removed a lot of content and asks students to go deeper in matters related to global modern history.

While Many teachers are understandably frustrated, as I have been at times in the last few months, I am taking this as an opportunity to evaluate and reflect on the types of assignment and assessments I give. In particular, I rarely give much attention to the history of Asia.

Whether intentional or subconscious, I tend to skirt around or speed through content areas that seem less important (read: not as interesting to me and content areas I know little about). Now that the overall course content has been halved, I need to develop some engaging learning activities and assessments in key areas of Asian history.

To that end, I have developed the first of several assessments in this content area. I developed a formative assessment based on the standard KC-3.1.III.D.ii,

“Buddhism and its core beliefs continued to shape societies in Asia and included a variety of branches, schools, and practices.”

This standard invites students to reflect on the shaping power of Buddhism in various Asian regions, in particular, Tibet, China, Japan, and South East Asia. This standard focuses on Cause and Effect, as well as Continuity and Change—critical Reasoning Skills AP wants students to develop.

Students are instructed to research the above standard or read two selections from the course textbook. Following their research, students will respond to the following questions:

(Q1) To what extent does Buddhism shape or influence society in Asia? (be specific!)

(Q2) Are there any more authentic branches of Buddhism? To what extent can those branches and new traditions that changed be considered “Buddhist”? What about other religions that have changed, like Christianity?

Loading...

Loading...

How students respond to these prompts is where this assessment gets fun! Students will use the verbal collaboration tool Flipgrid, a platform that functions as an educational Snapchat. Students will create video responses and be able to add stickers and apply filters to their videos using various tools.

Following their submission to Flipgrid, students are instructed to interact with their peers. In particular, students will conduct an online asynchronous discussion/debate concerning their responses to Q2.

To visit the Flipgrid webpage itself, click here.

By watching their peers’ videos and discussing the ideas, they will learn new areas of content. Student A may have focused on Tibetan Buddhism, while student B focused on Chinese Buddhism. Both will learn far more from each other as they interact through this assessment than if they had written a short essay in a traditional format.

I am a passionate advocate of Flipgrid, and I love using it for Metacognitive reflections and sharing summative projects. I believe that expanding into formative assessments and encouraging students to interact and discuss will increase overall learning.

Since I cannot and do not want to be the source of all information, empowering students’ voices is vital to student success.

Personalized Learning: A Wicked Problem Solved?

Posted on Dec 15, 2018 Leave a Comment

Personalized Learning is a wicked problem. That is, it is a problem so complex that it is nearly unsolvable. Personalized Learning, the educational philosophy wherein student learn and proceed through their content at their own pace according to their own interests and needs, is just one of these problems. My team and I, organized through our MAET program, tackled this wicked problem, both analyzing its complexity and asking questions that might reveal “what if” solutions to “solve” the educational quagmire.

To better understand the complexity of Personalized Learning, I created this infographic explaining what it is and what factors make it wicked.

While there are numerous complexities identified by the team, we developed four possible “solutions” to Personalized Learning.

- Schools should develop flexible learning spaces to replace the traditional layout of frontward-facing

- Schools should adopt an LMS in a tablet or computer 1:1 program

- Schools should shift to project-based/inquiry-based learning oriented around competency

- Schools should allow students to advance through content (AND COURSES!) at their own pace, regardless of what time of year it is.

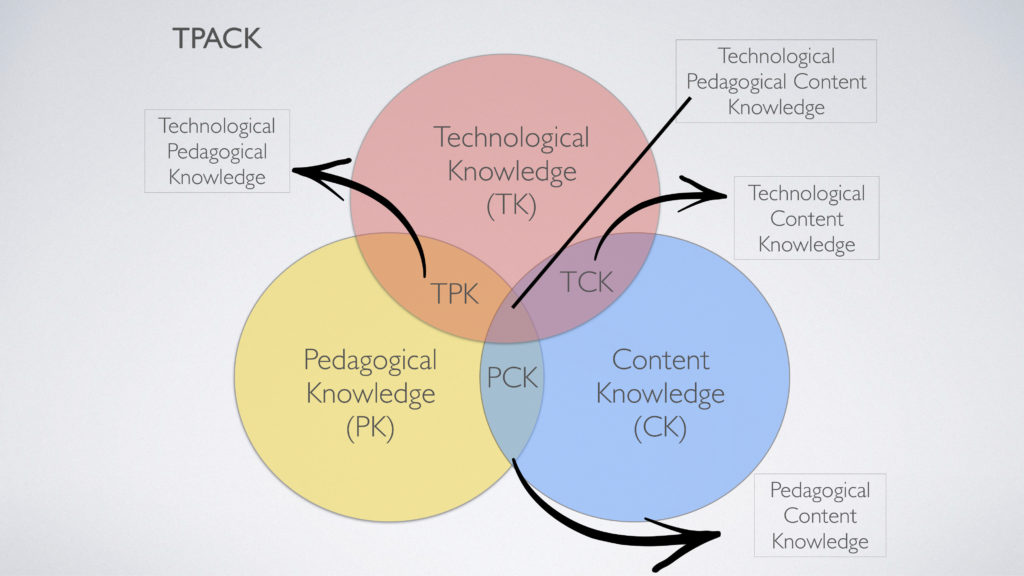

Integral to this solution is TPACK— the intersection between Content Knowledge, Pedagogical Practice, and Technology. This intersection is the only way in which a wicked educational problem can be solved.

In this case, solutions 1 and 4 are primarily pedagogical. Developing working spaces for student learning and structurally allowing students to advance at their own pace is central to the solution. Solution 3 is mostly content based. Teachers need to know their own field well enough to develop engaging and rigorous projects in partnership with their students. Finally, solution 2 is technology based. A 1:1 environment with an LMS would facilitate the rest! Without an LMS in a 1:1 setting, teachers would quickly become overwhelmed with all of the different pacing, work-flow issues, research accessibility, etc.

For more concerning our research, check out this video we created talking about our proposed “solutions” to the wicked problem of Personalized Learning.