A PASSION FOR CREATIVE HISTORY TEACHING

Posted on Dec 14, 2018 Leave a Comment

Starting out as a teacher, I went right back to that which I had become accustomed. Throughout college, professors would assign reading and then in class would tell us about the text in two hour lectures. I loved it. I enjoyed reading. I enjoyed talking about history. And so did most of the other students in the class—after all, we were all History majors. Once I started teaching History in High School, I was genuinely surprised when students were not engaged and excited about History class and the lectures I provided. I spend hours creating elaborate keynotes—one year I even recorded all my lectures and flipped my class. I believed that students would engage the online lectures and if I could just provide better lectures, students would engage. That never was the case. Students who participated, always engaged. Students who would not participate, would not engage with my lectures.

I found a passion and a burning question concerning this problem, and I have only become more obsessive about it.

Why is History class boring for so many?

How can I make History classes more exciting and engaging?

What if I stop lecturing all together and start creating inquiry and sensory-oriented project-based learning?

Warren Berger’s A More Beautiful Question inspired inspired their articulation. And wrapped within them are wicked problems in education that I am determined to solve (Berger, 2014, p.213)

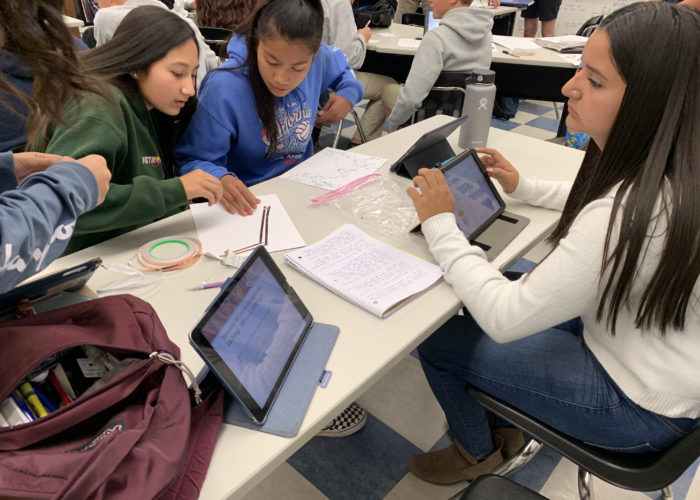

Once my school adopted an iPad 1:1 program, solutions to my questions began presenting themselves. We started using the iPad to conduct in-depth research, creative multimodal projects, and the information necessary to replicate the experiences of those in the past.

In the video below, I showcase new projects all adopted this school year, taught over the last five months since I started a Masters in Educational Technology at MSU. Several of these activities were inspired by the pedagogical challenges the program has facilitated.

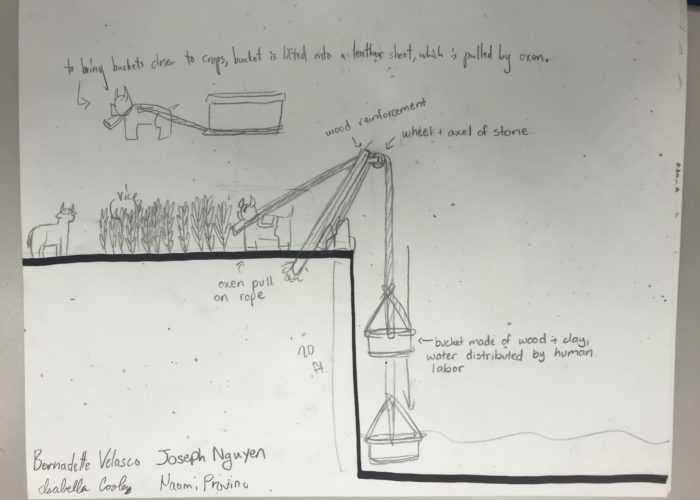

The cuneiform tablet creation, papyrus paper creation, and the cave painting simulation all required students to research what materials were used for their production. In the case of the cave paintings, students studied what pigments and materials were needed to create the paints. While somewhat low-tech, the students had spent weeks using iPads for guided research and inquiry leading up to these creations.

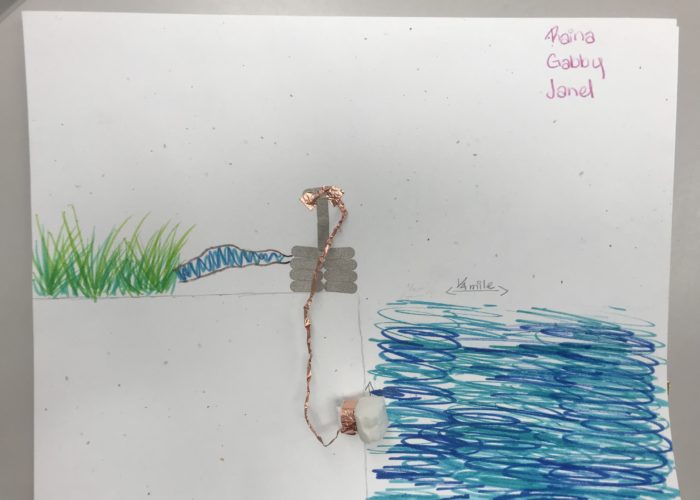

The final student creation displayed in the video is an interactive LED trade route map project that I developed in one of the first courses I took in the MAET program (CEP811 — Adapting Innovative Technologies in Education). In this course, we were asked to design a lesson plan in which students, in makerspaces, would create a tech-integrated project. This was the first time I tried the activity with students, yielding exciting results.

My students are engaged, excited, and more curious than ever before.

I am determined to make History exciting, engaging, and passion-filled.

And I hope that I will inspire my fellow teachers to do the same—to at least set aside some of the lecture time and engage the students’ passions and senses through creativity and creation, aided by their content, technology, and good pedagogy (TPACK).

In the words of Thomas L Friedman, “The old average is over” (Friedman, 2013). The hyper-connected world we live in now demands the best teachers and most passionate professionals to take the lead in their fields. I want to be part of that community shifting education into a better 21st century.

References:

Berger, W. (2014). A more beautiful question. New York, NY. Bloomsbury USA.

Friedman, T. L. (2013, January 30). It’s P.Q. and C.Q. as Much as I.Q. Retrieved December 10, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/30/opinion/friedman-its-pq-and-cq-as-much-as-iq.html

THE WICKED PROBLEM OF PERSONALIZED LEARNING: A SURVEY

Posted on Dec 2, 2018 Leave a Comment

Personalized Learning is an answer to the diverse needs, prior knowledge, interest, and skill of individual students. It is a customized and flexible approach to student learning in which students learn according to their own pace, making choices about their own learning, and adapting the material according to each student’s needs. However, several complexities make the prospect of implementing personalized learning seem impossible. Succinctly, personalizing learning would require that students have varying paces through the content, customized assignments, competency-based grading, more flexible workspaces, and technology-assisted tools for workflow and student learning.

Personalized Learning is an answer to the diverse needs, prior knowledge, interest, and skill of individual students. It is a customized and flexible approach to student learning in which students learn according to their own pace, making choices about their own learning, and adapting the material according to each student’s needs. However, several complexities make the prospect of implementing personalized learning seem impossible. Succinctly, personalizing learning would require that students have varying paces through the content, customized assignments, competency-based grading, more flexible workspaces, and technology-assisted tools for workflow and student learning.

As a possible solution, I and my team propose that schools redesign their work spaces and classrooms for flexible collaborative work (“makerspaces”) through which students may collaborate and create. We propose that students use an LMS (learning management system) like Canvas, D2L, or Schoology in a 1:1 laptop/tablet environment. We propose that student learning shift to student-centered and project-based, focused on competency and skill. Finally, (and perhaps most controversially) we suggest that classes shift from grade and age centered, to classes filled with students from all levels in the same discipline. For example, students in a Spanish class would be a mix of levels 1-4, advancing through the material at their own pace independent of the academic year. A student who works quickly may progress into level 2 while in the same academic year according to their own pace and needs.

I and my team have crafted a survey to address this complex problem as part of a study in my graduate program in educational technology at Michigan State University. I also hope that the results will inform discussions and planning for technology integration in the work we do together, and with students.

Please consider answering this short survey about Personalized Learning and our possible solution in your professional context. There are 14 questions. It should take you about 2 minutes to answer them.

10 COMPLEXITIES OF PERSONALIZED LEARNING

Posted on Nov 26, 2018 Leave a Comment

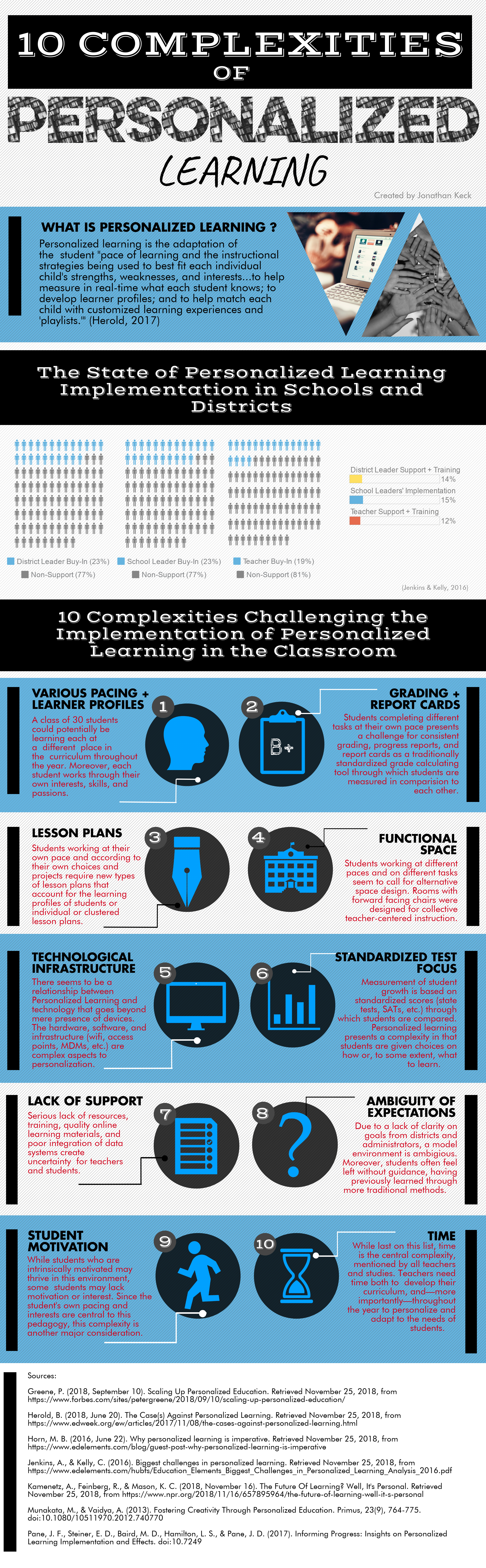

Personalized Learning is complex, so much so that it indeed is a wicked problem that seems to be impossible to solve. There are many layers of complexity and considerations from various stakeholders in the education of students—from parents to principals. Three central questions that drive further exploration of personalized learning are the following.

Personalized Learning is complex, so much so that it indeed is a wicked problem that seems to be impossible to solve. There are many layers of complexity and considerations from various stakeholders in the education of students—from parents to principals. Three central questions that drive further exploration of personalized learning are the following.

1. Why is there a need for personalized learning in the classroom today?

This questions probs the heart of the problem. Personalized learning has not emerged in a vacuum, but instead has been propelled as a solution to some educational issues. Better understanding those problems will help us understand the intent behind the personalized learning pedagogy and how it might be or might not be implemented

2. Why do teachers perceive that the personalized learning classroom environment will be an overwhelming challenge?

Due to the incredible complexities surrounding personalized learning, teachers seem to be overwhelmed by the idea of its implementation. This questions asks what specific things bring-on that anxiety and why. If this question can be answered, it may lead to solutions on how to implement personalized learning sustainably with the buy-in of teachers.

3. Why is the personalized learning structure just focused inside the classroom and not the entire school? (Pre-determined pathways, university requirements, standardized tests)

Personalized learning is focused on students advancing through course content at their own pace and through their own choices. However, due to the structure of education and batching students in rooms according to their age, students have little autonomy to advance beyond the class or grade. Moreover, the entire system of education is geared toward the assembly line education model. Unpacking why personalized learning has primarily focused on individual classrooms might help resolve some of the more significant issues that extend beyond the classroom.

These three questions will help focus further research into the wickedness of Personalized Learning. For a better picture of some, and by no means, all, of the complexities related to this pedagogy, check out this infographic on the 10 Complexities of Personalized Learning.

Killing Confirmation Bias in Ed Tech and Personalized Learning

Posted on Nov 18, 2018 Leave a Comment

Like most in this social media and smartphone age, I get a lot of my information—either news or stories—through Facebook and Twitter. Indeed, I don’t read the paper nor do I even go to a news website. Instead, I follow news agencies and “talking head” political analysts on social media. I must make a public confession that I, like many in our age, have retweeted or shared an article that I did not vet and did not read. The headline, central claim from the one sharing it, or the image or video itself drove me to share. Indeed, some bias within me had been confirmed, and my immediate instinct was to hit retweet. Rarely do I hover over the button, wondering if it is true. No, it must be true, and everyone needs to be outraged like me or see that I was right! And like most, there have been several times when one more critical than I has responded back with a “Fake News” comment or a link to Snopes. I hate to admit it, but I’ve had to walk back a shared post on more than one occasion.

Like most in this social media and smartphone age, I get a lot of my information—either news or stories—through Facebook and Twitter. Indeed, I don’t read the paper nor do I even go to a news website. Instead, I follow news agencies and “talking head” political analysts on social media. I must make a public confession that I, like many in our age, have retweeted or shared an article that I did not vet and did not read. The headline, central claim from the one sharing it, or the image or video itself drove me to share. Indeed, some bias within me had been confirmed, and my immediate instinct was to hit retweet. Rarely do I hover over the button, wondering if it is true. No, it must be true, and everyone needs to be outraged like me or see that I was right! And like most, there have been several times when one more critical than I has responded back with a “Fake News” comment or a link to Snopes. I hate to admit it, but I’ve had to walk back a shared post on more than one occasion.

But this tendency is not isolated to me alone. In an age of outrage, the dominating force of confirmation bias looms. Eli Pariser (2011), author of the Filter Bubble, and James Paul Gee (Z) author of The Anti-education Era, have argued that the internet creates for us a warm cocoon in which one tends to surround themselves with confirming voices, like-minded people, and supportive news agencies. What is relevant to us, has led to information isolation.

Similarly, like a hissing-vampire confronted with garlic or the demonically possessed at the sight of the cross, Fox News or CNN may repel the hyper-political at its mere mention. However, giving room for disagreement and multiple perspectives and voices in good faith in necessary for our intellectual health. And likewise, bursting the filter bubble is necessary not just in politics, but in education.

Students need these same skills and a healthy and critical attitude toward information vetting. We must help them navigate information in the age of “Fake News,” confirmation bias, and outrage retweet culture.

Students need these same skills and a healthy and critical attitude toward information vetting. We must help them navigate information in the age of “Fake News,” confirmation bias, and outrage retweet culture.

But how do I expect to guide my students to a place that I refuse to go myself?

And while politics is rife for disagreement, so too is the field of education. As a technophile and (unfortunately) labeled the tech guru at my school, I have a bias concerning the role of tech in the classroom. To make matters worse, I teach in disciplines that are slow to embrace or adapt to new education innovations. While not as bad as the Mathematics department (sorry math enthusiast!), the Histories and Classics are slow—if not outright resistant—to change. I teach AP Histories and Latin and have a love for all things antique. These two loves make me an odd fellow with feet in two very different camps. On the one hand, I nerd-out with the STEM teachers on the latest innovations, and on the other, I lament the decline of reading Plato and the dwindling number of students taking Latin.

My twitter feed is dominated by tech-advocates, teachers with Google class tips, and pedagogical innovators calling for the personalized learning revolution. I have not had many voices from the classics because, frankly, I disagree with them. I understand the merits of reading Plato and learning Latin, but I do not see the demon in the device sitting on my student’s desk. Outright calling for Plato over iPad, there is a movement of classical education advocating for low- or no-tech education. Perhaps they have a point, and we’ve dove headlong into tech with all that it promises. Perhaps personalization will not be able to deliver on all that it boasts. After all, maybe there is value in the traditional methods and uniformity of a single pathway concerning core content and skills.

To give space to these voices, I have followed several schools and advocates for low- or no-tech classical education. I have also pursued a variety of views—both critical and supportive of personalized learning.

Here are the new voices I’m following on Twitter:

Seeing their best intentions, I have chosen not to outright dismiss their position as wrong-headed. Instead, I am approaching them as one who does not know everything and can learn why they came to the conclusions that they did. Whether this transforms my approach, only time will tell. But it indeed challenges my assumptions and forces me to become a more thoughtful teacher.

LINKS TO NEW VOICES ON TWITTER:

The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America — low/no-tech education advocates

Sherry Turkle — Author and tech critic researching the negative social effects of technology

Ridgeview Classical Schools — Organization dedicated to low-tech classical education

Tristan Harris — Co-founder, Center for Humane Technology. Address the global threat posed by runaway attention-maximizing technology.

Daniel Willingham — critical of personalized learning and giving students too much choice

Institute for Catholic Liberal Education — Organization advocating No/low-tech and critical of standards-based education

Alex Hernandez — advocate for personalization

Benjamin Riley — critical of personalization

Summit Schools — network of public schools focused on personalized learning

John F. Pane — author of recent empirical study on Personalization and found it resulted in better student performance. He is an active researcher on personalized learning.

WORK CITED

Gee, J.P. (2013). The anti-education era: creating smarter students through digital learning. New York, NY. St. Martin’s Griffin.

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You. Westminster, London. Penguin.

INQUIRY BASED LEARNING AND THE HIGH SCHOOL HISTORY CLASSROOM

Posted on Nov 12, 2018 Leave a Comment

The now iconic scene of the monotone economics teacher played by Ben Stein in Farris Bueller’s Day Off hilariously encapsulated the collective experience High Schoolers endured in a Social Science classroom—perhaps any class. The premise of the film strikes a chord with many students: school is boring, and we’d rather feign sickness than attend. As any teacher can attest, we are no strangers to the blank stares and mindless expressions of students—especially High Schoolers. By way of reference (or for a laugh), check out the economics lecture from this famous film.The scene is funny because it rightly reflects the traditional student experience in High School—especially in the social sciences. Boring lectures, seemingly irrelevant facts, and forward-facing information download only to be regurgitated on a test at a later date. But what if the History classroom could be exciting? What would it take for students to wake up excited to come to class that day and disappointed when the bell rings, and students need to leave World History for one of their other courses? A fundamental shift in the way learning occurs in the classroom is required.

Warren Berger explores a pedagogical shift through igniting student curiosity by inspiring inquiry in his book A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas. In his chapter Why We Stop Questioning, Berger argues that “our current system of education does not encourage, teach, or in some cases even tolerate questioning…” (2016, p. 46). And since questions are stifled, students become passive consumers of information pre-determined by the teacher and spoon-fed through lectures and handouts that reinforce rote memorization of facts. However, our current technological shift and the rise of Google and the looming A.I. will make this sort of rote-memorization education obsolete.

A quiet but powerful education revolution is growing, centered around Project-Based and Inquiry-Based learning. Deborah Meier, a designer of Inquiry learning at Central Park East Schools, advocated for just such a shift back in the 70s. She wanted to shape students into “critical thinkers and problem solvers” (Berger, p.51). And while critics may see a chaotic and undisciplined environment, a learning experience centered around students and their inquiry looked more like excited engagement rather than a library or graveyard of inquiry like the traditional classroom (Berger, p.53).

Berger, reflecting on Meier’s classroom environment, argued that she sought to “extend the kindergarten experience throughout all grades” (2016, p.52). In those formative years, students are given far more freedom to experience and learn, asking questions and not being confined to strict pacing and testing. Indeed, Berger also lauds the Montessori Schools that emphasized student-directed learning, projects of passion, and guided inquiry (2016, p.54). As a whole, these learning environments encourage inquiry and creativity, two invaluable skills that will shape the future work environment.

As a new teacher having been produced by these same traditional pedagogies, I quickly slipped into teaching much like Buller’s infamous economics teacher. In reality, I was far more animated and spend hours creating elaborate Keynotes. In my first two years, I lectured almost every day in that World History class full of Sophomores. Over and over, I saw either blank stares or otherwise interested students that did not know how to engage in the art of inquiry and think like a Historian. It was then that I realized something needed to change. It has been a long road, with much trial and error. What I know is that I, like Meier, want to create a learning experience for my students filled with passion, inquiry, and an environment filled with productive and exciting collaboration and creation.

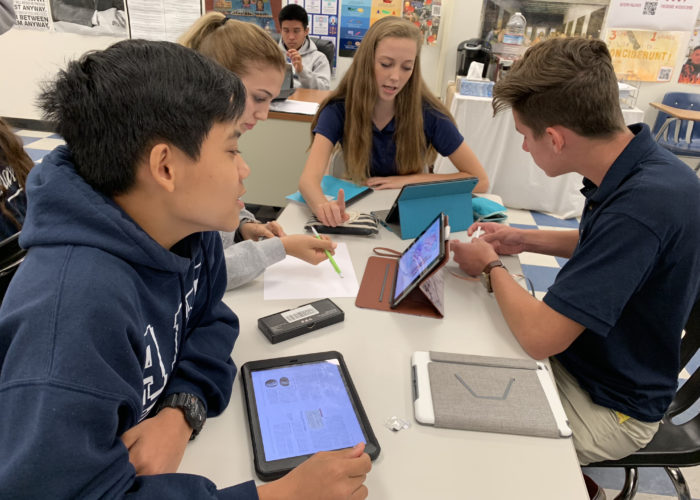

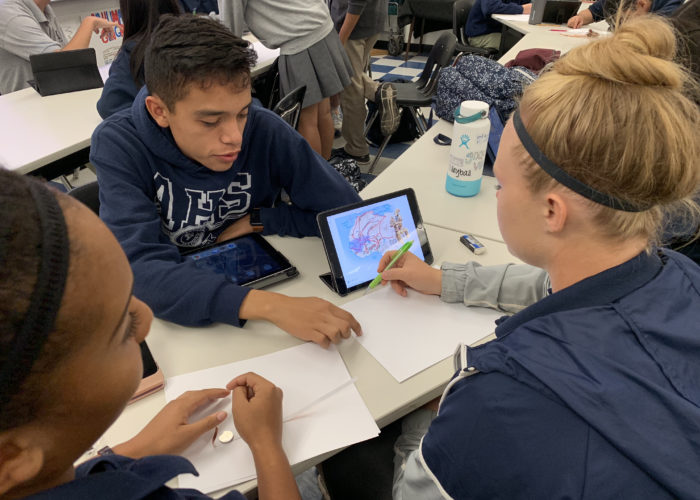

Indeed, this last week I designed a multi-day project/inquiry-based learning activity in which students researched, designed, and created interactive trade maps. Teams of students chose a region of the world they believed most important for trade. They investigated what ports existed and what routes were traveled. They artistically created and designed the map itself and designed LED lights and copper tape to illuminate essential ports.

I would have never imagined teaching in this manner years ago, but the excitement and creativity of students has been electric.

However, I have not arrived yet. When I read about “extending Kindergarten into all grades” and Montessori schools, I wonder what recreating that learning environment in my classroom would look like. What would it look like to create a Montessori High School or a truly Project-Based and Inquiry-based learning environment?

I’m excited to find out.

Berger, W. (2016). A more beautiful question: the power of inquiry to spark breakthrough ideas. New York: Bloomsbury.

Pmw8000. (2011, Dec 29th). ‘Anyone, anyone’ teacher from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uhiCFdWeQfA

FLIPGRID AND DYSGRAPHIA MODIFICATION

Posted on Nov 5, 2018 Leave a Comment

Flipgrid fever has struck many teachers. One need only check the hashtags #flipgridfever to catch a glimpse of the excitement. In the age of Snapchat, memes, and gifs, students can often feel disengaged with old-school handouts. Flipgrid is an app used on Microsoft, Apple, and Google products that allow teachers to create digital classrooms for engagement and dialogue. Teachers can post written, verbal, or video prompts to encourage discussion, and students create video responses, both to their teacher and to other students. Indeed, the potential for engagement and learning is huge, and the verbal expression of student thought is rather exciting. And this platform is not just limited to a particular age group but can be customized for the needs of all classroom, courses, and students.

Flipgrid fever has struck many teachers. One need only check the hashtags #flipgridfever to catch a glimpse of the excitement. In the age of Snapchat, memes, and gifs, students can often feel disengaged with old-school handouts. Flipgrid is an app used on Microsoft, Apple, and Google products that allow teachers to create digital classrooms for engagement and dialogue. Teachers can post written, verbal, or video prompts to encourage discussion, and students create video responses, both to their teacher and to other students. Indeed, the potential for engagement and learning is huge, and the verbal expression of student thought is rather exciting. And this platform is not just limited to a particular age group but can be customized for the needs of all classroom, courses, and students.

Indeed, teaching an Advanced Placement History class is wonderful and difficult. Teaching itself is a wicked problem, weaving objectives, standards, differentiation, and a slew of other things to consider. But layered on top of these considerations are the demands specific to AP and preparing students for academic success as measured through the standardized test. The AP Histories require students to develop the HRS—the Historical Reason Skills, closely associated with previously published works on Reading Like A Historian and the Common Core Reading and Writing Standards. These skills emphasize both reading and writing practices and advanced reasoning. Concerning the former, students are asked to read both primary and secondary sources, especially those that address similar topics from various points of view and often those that contradict one another. Moreover, the AP curriculum encourages these students to consider cause and effect, especially multi-faceted and complex events. Furthermore, students consider continuity and change, analyzing what changes and what remains contiguous in civilization and why. Finally, students develop a nuanced ability to compare and contrast historical events and movements.

The AP history class provides numerous opportunities for students to grapple with complex problems such as those listed above. In years past, my AP World History class and I read excerpts from Hammurabi’s Code and the Ten Commandment’s in the Exodus text. I provided a Venn diagram graphic organizer to assist them in making comparisons. This assignment is complex. While students had help from both their peers in small groups and me, several students struggled. The assignment asks that students read and digest complex ancient laws and compare not only the obvious similar laws but the societal ethics that underpin the motive for writing these laws. One student in particular especially struggled. His writing was somewhat sloppy and borderline illegible. Moreover, while working with him to read the text more closely, he really struggled with reading the material, often jumbling words. This student had no problem explaining the material we discussed and even had some interesting insights into the implications of these law systems. He clearly understood the material but struggled with the medium of reading and writing. After consulting with the counselors and some testing, he was diagnosed with Dysgraphia.

Dysgraphia is a learning disorder in which an individual’s ability to write is severely lower than their grade level or what would be expected at their cognitive level. According to Peter Chung and Dilip Patel, this disorder is often associated with “difficulty in writing at any level, including letter illegibility, illegibility, slow rate of writing, difficulty spelling, and problems of syntax and composition” (2015, p. 27). Dysgraphia is often also associated with other neurological and developmental disorders, 30-47% of the time associated with dyslexia (Chung & Patel, p. 30). Chung and Patel advocate for several accommodations and modifications to assignments. A common accommodation I have used with students is allowing them to type their papers or handouts using a school-issued iPad. My school is an iPad 1:1 learning environment, which makes accommodations like these much more accessible. But Flipgrid would serve as an excellent modification tool, allowing a student to express their thoughts verbally. Indeed, Chung and Patel state that oral reports and presentations would be ideal methods for students with Dysgraphia (2015, p.32).

Instead of writing a response to a Historical Reasoning Skill prompt from a past AP United States History exam this last week, I posted the question to Flipgrid. The complex problem I gave them required that they evaluate the extent to which commercial exchange systems such as mercantilism fostered change in the British North American economy in the period from 1660 to 1775. Students responded by creating meaningful and engaging videos that provided an argument and historical evidence by which they might defend their thesis. While modifying the assignment using Flipgrid sidesteps the writing and allows students to communicate through a medium that will help build their confidence, the tool can never replace writing as a whole. Using Flipgrid is helpful and fun, but other solutions for accommodations, like typing a paper, still need to be utilized. Nevertheless, this platform seems to not only serve as an ideal tool for students with Dysgraphia, but for all students.

REFERENCES

Chung, P., & Patel, D. R. (2015). Dysgraphia. Int J Child Adoles. Health, 8 (1), 27-36.

ASSESSING CREATIVITY: A REFLECTION ON GRADING MAKER PROJECTS

Posted on Aug 17, 2018 Leave a Comment

“How am I going to grade this?” That was the first thought that came to mind once the creative and fun designs lay on my desk. This was the first time I used a Design and Making activity in my AP World History class. I was so excited and eager to design and implement this activity in my class that I hadn’t considered how I was going to assess the students’ work.Since this was primarily a creative thinking assignment, I wasn’t sure how precisely I would evaluate and assign grades to each of these collaborative solutions to my Ancient Irrigation PBL activity. As an aside, if you’d like to read about the actual activity and my first attempt at a maker assignment, see this reflection on my first implementation of this activity.

Honestly, I had no idea how to effectively and fairly judge and assign grades to these students. I knew implicitly that some of the activities were more creative and better designed. But it seemed wrong to assign a mark that might affect their overall grade in the course. But upon reflection and after reading Grant Wiggins’ (2012) thoughts on grading creativity, I realized that I had already assessed these students’ work. I feared to assign grades because I felt my reasoning was “squishy” and based on a “gut instinct.” How would I explain a low mark to a disgruntled student or parent other than “I know creativity when I see it?” Grant Wiggins (2012) provides an excellent rubric for assessing creativity right here, and I will certainly be using it! In his post explaining the rationale behind assessing creativity, Grant argues that “It is vital when asking students to perform or produce that you are crystal-clear on the purpose of the task, and that you state the purpose…to make clear that the purpose is to cause an intrinsic effect, not please the teacher…” (Wiggins, 2012). The design process and creation must be assessed, and thus, in the case of my PBL activity, the creativity of the solutions must be assessed.

But in addition to the above rubric, I also provided opportunities for students to self and peer-assess their projects. As the students collaborated, I walked around the room and asked them to question what obstacles their designs might face and how well-thought through were their solutions. This formative assessment gave students permission to question their own work and ponder how it might be improved. These sorts of assessments are vital to learning.

At the end of the project, I took pictures of each of the projects and created a Google form that anonymously asked which design was most creative and which design was most likely to work in the real world. This low stakes peer-assessment facilitated a group discussion on why the common class voted in the way that they did.

The Google Form for peer-assessment of the AP World PBL

These types of assessments are supported by the ultimate goals of teaching innovatively and creatively. Under the old vanguard of “Skill and Drill,” the “Test-Prep Academies” lecture, memorize, and assess rot memorization. But as James Gee (2010) so insightfully observes, “Words are tools for problem-solving, they’re not just facts to do trivial pursuit with” (Gee, 2010). The terminology and information of a subject are important, but not necessarily intrinsically. That information has a utility for some other purpose. As a whole, that purpose is thinking creatively, problem-solving, creating, and designing. To that end, assessing creativity is vital to forming students into the innovators of tomorrow.

But this raises more specific questions related to my own discipline. What is the purpose of a Social Science class? Science and Engineering seem apparent, but less so for Language Arts and the Social Sciences. I am convinced, however, that a cross-curricular “renaissance” in education is coming. As observed by Eric Isselhardt (2013) concerning Green Street Academy, creating cross-collaboration through varying disciplines in well-designed PBL projects is the way forward. Rather than looking at one’s class as an island, having teachers create “a comprehensive, cross-curricular, common-core-derived standards map” that facilitates designed projects that span multiple courses is genuinely transformative (Isselhardt, 2013). I want to explore this teaching design with my own team. Like Green Street, my own school serves an urban and academically underperforming community. If this creative approach worked for them, there is no reason it would not work for us.

Assessing creativity and cross-curricular design and maker projects is the future of education and I, for one, am excited.

References

Gee, J. P. (2010, July 20). James Paul Gee on Grading with Games. Retrieved August 15, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JU3pwCD-ey0

Isslehardt, E. (2013, February 11). Creating Schoolwide PBL Aligned to Common Core [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.edutopia.org/blog/PBL-aligned-to-common-core-eric-isslehardt

Wiggins, G. (2012, February 3). On assessing for creativity: yes you can, and yes you should. [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://grantwiggins.wordpress.com/2012/02/03/on-assessing-for-creativity-yes-you-can-and-yes-you-should/